By Gary Deane

Though unlisted among Eddie Muller’s storied Dark City Dames or Karen Burroughs Hannsberry’s Bad Girls of Film Noir, Hollywood actress June Havoc featured in six pitch-dark crime dramas over a five-year period which might count her in as a true “sister under the mink”.

Havoc’s personal and professional story up to that time is legend, revealingly told by the actress herself in two candid autobiographies, Early Havoc (1959) and More Havoc (1980). Those who know the gorgeously gaudy Jules Styne/ Stephen Sondheim Broadway musical Gypsy will remember the refrain “My name is June, what’s yours?”, delivered by Baby June, the curly-haired moppet. The show was inspired by her early life on the vaudeville circuit and that of her famously ambitious stage mother, Rose Thomas Hovick, and older sister, Rose Louise, who became Gypsy Rose Lee, celebrity burlesque queen and striptease artiste.

Although Havoc acknowledged the greatness of Gypsy as a musical production, she otherwise contested it, asserting that it was a hurtful misrepresentation of her own part of the story. However, it seems that from a very young age Havoc had had to fight hard for her share of whatever was owed, including a mother’s love.

Havoc was born in Vancouver, Canada in 1912 but moved stateside with her mother and sister while still an infant. At age two, she was playing bit parts in silent films. By age five, she was a headliner on the Keith Orpheum Circuit in vaudeville earning $1500 a week.

But Mama Rose kept June on the road well past the cute stage. Frustrated and weary of the grind, Havoc tried to escape when she was fifteen by marrying a boy in the show. However, the marriage was short-lived and she went back on the circuit until it collapsed early on during the Great Depression. To survive, she gutted it out in dance marathons, the experience of which she evoked vividly in a 1963 play Marathon 33 which garnered Tony nominations for both its direction and for Julie Harris as a young vaudevillian named June.

In 1936 at age 23, Havoc began to appear regularly in Broadway musical comedies. A big break came four years later in 1940 when she starred alongside Gene Kelly as Gladys, a nightclub performer in the Rodgers and Hart hit Pal Joey. One critic wrote, “June Havoc, who has been Gypsy Rose Lee’s sister so long she is sick of it, came into her own as a musical comedienne.”

Now into her twenties, Havoc had developed into a striking blonde beauty and a natural stage actress. At this point, Hollywood could not stay away. In 1941, Havoc made an impressive feature film debut in Four Jacks and a Jill with Ray Bolger and Anne Shirley. The following year she starred with Bert Lahr and Buddy Ebsen in Sing your Worries Away in which she took off her clothes in a pointed take-off of her sister. Other supporting parts followed in My Sister Eileen (1942), a successful Fox musical Hello, Frisco (1943), and Brewster’s Millions (1945), thought to be the best of the several screen versions of the popular play.

Though the roles were small, her performances were all well-received. But Havoc wanted larger parts in less airy productions. She’d starred earlier on Broadway as Miss Sadie Thompson in Rouben Mamoulian’s re-working of Rain which had provided her the experience and the confidence to contemplate more serious roles. Then in 1947, she was cast in Elia Kazan’s Gentlemen’s Agreement as Gregory Peck’s secretary, a self-hating Jewess who had changed her name to the more ethnically-neutral ‘Elaine Wales’ in order to work for Peck’s virulently anti-Semitic magazine. Though Havoc received nothing but praise for her performance, nothing bigger came of it.

Havoc was now 35 years old and neither a fresh face nor an established attraction. She’d also elected not to be put under studio contract so as to be able to continue to accept stage work. And in October 1947, she flew to Washington with a group of actors and directors that included Gene Kelly, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, and Danny Kaye to protest the activities of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Neither did anything to help to her career. Nevertheless, Havoc still was able to find work, though limited to second-tier A titles and lesser B productions. However, the silver lining was that she was at least as big as the pictures on offer and leading roles were now available to her.

The first of these would be in Intrigue (1947), one of the six classic film noirs in which Havoc would feature.

Intrigue is an ‘adventure noir’ in which Havoc plays a bewitching tiger-woman, Madame Tamara Baranoff, who heads up a black market operation in post-war Shanghai. Sharing the bill is George Raft as Brad Dunham, former US Air Force pilot with a tarnished service record who contracts to set up a smuggling operation within Havoc’s territory. Dunham sees an advantage in their working together and makes an approach, business first, then pleasure. t the same time, Dunham finds himself romantically pursued by Linda Parker aka Linda Arnold (Helena Bonham). Parker’s later revealed to be investigating her father’s mysterious disappearance while serving under Dunham, thus thickening the plot.

Intrigue was directed by journeyman Edwin L. Marin who’d previously worked with Raft on Johnny Angel (1945), Mr. Ace (1946), and Nocturne (1946) and later would make Race Street (1948) with him. The film starts out promisingly, in large part due to cinematographer Lucien Androit’s beautifully moody and evocative camerawork. Androit, a prolific Hollywood lensmen, earlier had shot Jean Renoir’s The Southerner, the best of the French director’s handful of American-made films.

However, Intrigue soon sags under the weight of a pedestrian script and the burden of Raft’s dour and charmless persona. The actor by this time was several years past his sell-by date and though only in his late 40’s, appears older and much the worse for wear. The street swagger and bravado looks cooked-up and any presumption of Raft as a romantic lead is just that. It couldn’t have been easy for the far younger Bonham to have to lock lips with the reptilian Raft, but she manages.

Meanwhile, Havoc in her first starring movie role mostly looks uncomfortable, especially during some of the laughably pulped-up exchanges with Raft:

Her: “How do you know you’re safe with me?”

Him: “How do you know I haven’t got a gun?”

Her: “Because your clothes fit much too well.”

Him (leering): “It’s plain to see you haven’t got a gun either.”

If there’s supposed to be chemistry happening between the two, then the experiment is a dud.

On the other hand, Havoc probably was not the best choice to play the exotic femme fatale, Madame Baranoff. Havoc could be a wonderfully tough cookie but she was strictly a made-in-America tough cookie. She didn’t possess the kind of icy hauteur the part called for and comes across as stiff and emotionally withdrawn, especially in the difficult scenes with Raft. Otherwise, Havoc is an arresting presence in Intrigue and much of the movie’s budget obviously was assigned to putting her into a succession of stunning outfits, a different one in every scene. The wardrobe and design feature large in the film. Raft himself is stylishly attired though it’s apparent that an effort’s being made to hide the actor’s widening girth. However, in the end, the movie made it plain what would work for the attractive, spirited actress and what wouldn’t.

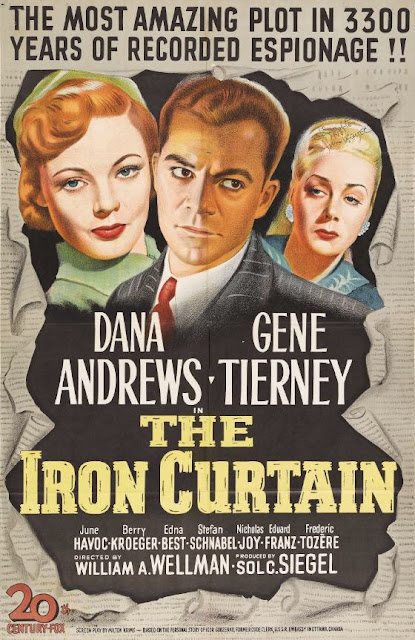

Havoc’s next starring picture was an A title, The Iron Curtain, an urgent, well-crafted ‘spy noir’, directed by William Wellman and starring Dana Andrews and Gene Tierney.

Andrews plays a diplomat attached to the Russian Embassy in Ottawa who decides to defect with his wife (Tierney) and their infant child. Based on the story of real-life spy Igor Gouzenko, the movie is an exciting and credible anti-commie saga (a full account of the Gouzenko affair is found in the book, Gouzenko: The Untold Story, by John Sawatsky, a Canadian investigative journalist).

Havoc’s in a supporting role, but it’s one critical to both the development and understanding of the story. Nina Karanova (Havoc) is an embassy clerk ordered by the embassy and military officials to befriend Gouzenko and test his loyalties, both professional and personal, when he first arrives in Ottawa (while his wife remains in Russia). Karanova does as ordered. She asks Gouzenko to go for drinks, have dinner, and go out dancing. The evening finishes with her inviting him to her apartment. Igor, now drunk, seems delighted with the way things are going. But Nina then begins to press him about his Embassy responsibilities and even his wife, asking him whether she is “as beautiful as I?” Gouzenko, suspecting that he’s being played, responds to her in a drunken rage, “Your beauty is a thing carved out of granite with no body or soul!”

It’s a disquieting moment. Up to then, Gouzenko has treated Nina decently and she’s begun to feel close to him. But Nina is vulnerable, more used to being abused and belittled by her male superiors (When she gets her instructions to test Gouzenko’s loyalty, one of the officials Major Kulin (Eduard Franz) crudely propositions her. When she ignores him, he says with contempt, “Cold fish, isn’t she”?) Nina has learned to be calculating and duplicitous as she responds to dictated beliefs. Havoc convincingly negotiates the treacherous terrain of the The Iron Curtain and comes closer to hitting her mark as a compelling femme fatale.

Her next noir assignment came only months later with Chicago Deadline (1948), the story of a reporter’s attempt to find out the truth about a beautiful woman discovered dead in a seedy South-side Chicago boarding house.

Directed by Lewis Allen (Desert Fury 1947, So Evil My Love 1948, Sealed Verdict 1948, Appointment with Danger 1951), the film stars Alan Ladd as Ed Ames, a reporter who uses the woman’s address book to try and track down those who may have known her, or at least of her. Ames soon finds that in either case, no one can or is willing to tell him much at all. Gradually, professional curiosity turns into personal obsession and what little he’s been able to learn about the mysterious woman – identified as Rosita Jean d’Ur (played in flashback by Donna Reed) – has only come to frustrate and disturb him. Ames rants, “She’s a dame, a saint, a gangster’s girl, and a sister who remembered birthdays! Who is she?”.

Meantime, he meets Leona Purdy (Havoc) at a party. Leona’s a little drunk and a little needy and more than pleased to get some attention from Ames – at least until he asks her about Rosita. She quickly backs off and says “You do get around”. Ames presses her and she gives way, confessing, “I don’t get along with champagne and you shouldn’t have looked at me like that”. She tells him that she only met Rosita once or twice and that was a couple of years ago. She also teases him, saying “As a reporter you’re a dud. Why, even I could have got much more out of me.” Leona is playful and unconcealed in her feelings. She’s also very aware and understands how much Ames is in thrall to Rosita and that if she’s going to be with him, she has no choice but to play her cards as dealt. Though Leona perseveres, she gets little in return for her loyalty and affection. The best Ames will do is to tell her she’s “a good kid”. But Leona sticks with him until the end, the funeral of Rosita. Ames has dragged himself there while still recovering from a gunshot wound and Leona realizes he’ll die if he doesn’t get back to hospital. When he resists, she says to him with regret, but without hesitation, “If you won’t do it for me, Ed, I know she would want you to.”

It’s a sorely sentimental scene, but then too often Chicago Deadline tends to be maudlin when it should be mordant. However, if the movie has problems, Havoc’s performance isn’t one of them. She’s the most genuine thing in the film. While Havoc lets us feel sympathy for Leona, she leaves little space to feel sorry for her. Despite her too-ready allegiance to a fated relationship, Leona refuses to demean herself. In Chicago Deadline June Havoc’s noir persona begins to take full form: intelligent, realistic, resilient, and tough-minded. It’s a man’s world, but Leona has learned to live in it, sometimes on its terms, sometimes on hers. She sidelines disappointment and rejection with smart humor. When Ladd’s inattention gets to her, she wisecracks, “Honey, what did you take as a sedative before you met me?” Havoc is undefeated in Chicago Deadline and more than just a “good kid”; she’s a marvelous and memorable film noir dame.

Havoc got to put that best dame forward again in her next film, The Story of Molly X (1949), a crime drama and ‘prison noir’ that’s become one of the actress’ best-known films.

Molly is a glamorous, brass-knuckled broad who’s taken over her lover’s crime outfit in San Francisco following his murder. She’s determined to keep his operation and find out who killed him. After a jewel robbery that goes bad, she discovers the culprit was Rod Markle (Elliot Lewis), one of the gang’s inner circle. Molly soon takes care of him.

The robbery, however, lands Molly at the women’s state prison in Tehachapi, a California state correctional institution. Molly couldn’t care less about becoming a model inmate - until she hears that her dead boyfriend’s partner, Cash Brady (John Russell) has been charged with Markle’s murder and is facing the chair. Molly then plays by the rules in order to earn early parole and so she can get rid of evidence that points directly to her.

Havoc is terrific as Molly, the toughest dame in the prison dorm. She lays a ferocious beating on Lewis’s double-dealing girlfriend, Anne (Dorothy Hart), a rat recruited by McGraw to help get proof of Molly’s involvement in the Markle killing. However, Molly X extends beyond being a briskly-told hard-boiled crime drama. The film, written and directed by life-long progressive Crane Wilbur, takes up the cause of inmate reform and rehabilitation over criminal punishment. Wilbur brought the same conviction to several other prison films, including Canon City (1948), Outside the Wall (1950), Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison (1951), and House of Women (1962).

The movie goes further as an embittered Molly recounts to a cellmate how as a young girl she’d been sexually assaulted by her stepfather and had run away and turned to crime to survive. The inference that sexual abuse could be a root cause of anti-social and criminal behavior was a brave proposition for the time.

Molly X also breaks ground when Molly takes of control of the gang in the movie’s opening scene at the Top of the Mark Lounge in San Francisco. Molly moves on this decisively and without drama, despite evidence of threats coming from Anne. To today’s audience, female agency is taken for granted; however, prior to Mollie X, examples of such unapologetic assertiveness and authority hadn't been seen on the screen since Pre-Code days.

It’s a treat to see Havoc get the chance to act out in a lead role with as much force as she does in Molly X. Here was an actress with guts who’d come up the hard way and survived and whose best films were those in which she was able to fold that experience into her performances. Molly X leaves no doubt as to Havoc’s special qualities as an actress, running the gamut from hard-boiled defiance to heartfelt contrition, as convincingly as the script might allow. The film’s sentimental ending is a letdown, given all that’s come before. Despite that, The Story of Molly X ranks as a first-rate little B noir.

On its heels came Once a Thief, a wonderfully punchy, no-frills B noir with a one-step-ahead storyline.

Told in flashback, the movie has Havoc in the lead as Margie Foster, a factory girl who in desperation turns to shoplifting after getting laid off from her job in San Francisco. After Margie nearly gets busted, she heads for Los Angeles and once there decides to go straight. She takes a waitressing job in Eddie’s Cafe, where she meets Flo (Marie MacDonald), who’s also down on her luck. The two become friends and move in together. Margie then runs into Mitch Moore (Caesar Romero) while dropping off a dress at his dry cleaners. Moore, who looks good, is just a cheap hustler and shameless womanizer. When he happens to get a sneak peek at Margie’s bankbook – which shows a healthy balance – he’s over her like ants on picnic blanket. Margie falls hard for Mitch, convinced he’s going to get her to the church on time. However, as she later laments in voice-over, “Instead of a wedding ring, I ended up with a handcuff on my wrist”. Mitch reveals himself by stealing every penny she has and then turning her into the cops for a crime committed earlier in San Francisco just to rid of her. Molly goes to jail, but later escapes and is hellbent on revenge.

Mitch is breath-taking in his disregard for anyone but himself. Too lazy to be clever and too selfish for his own good, Mitch will get what he deserves but along the way does dreadful damage. When his former girlfriend, Nickie (Marta Mitrovich) begs him to stay with her, he says, "You could drop dead for all I care" – after which she kills herself. When Mitch finds her with her head in the oven, all he has to say is, “I don’t know what gets into a dame like that”. He finds a suicide note to which is clipped her last ten dollars. He stuffs in pocket and smiling, goes straight to the bar telling the barkeep to, “Set ‘em up Eddie, this round’s on me!”.

Mitch is another of the cold-hearted cads and small-time chiselers that Caesar Romero had been playing since his debut in The Thin Man in 1934. However, Mitch with his cocksure allure is in a whole other league. Her friends try to warn Margie off, including the brassy, down-to-earth Pearl who’s always got a good word for her: “So you’re hanging on by your eyelashes, a pretty gadget like you. You got nothing to worry about. Just stick around me. Life is a merry-go-round and someday you’re going to latch onto the ring.” Then there’s Gus (Lon Chaney Jr.) who minds the store for Mitch and runs a gambling room at the back. But while he’s Mitch’s faithful wingman, he at least has a heart where his boss has a hole. And for her part, Flo never stops trying to warn Margie about Mitch, finally telling her when she’s in jail to “just forget him”. But now Margie knows where she really stands, that’s not going to happen.

If there’s one film for which director W. Lee Wilder would never need to apologize, it’s Once a Thief. Done on a minuscule budget, it’s a gritty and honest B noir gem with a fault-proof cast and a hard-knuckled and determined script that’s willing to follow through on the obvious. Though Once a Thief has been compared to The Blue Gardenia, it’s a poor comparison, given the latter’s labored plot, carelessly-written characters, and Anne Baxter’s flatulent emoting. In contrast, Havoc keeps a lingering distance, even during the most intense moments. She cuts against the grain as she’s able to elicit empathy without ever coming close to emotional pandering or soapy sentimentality.

Havoc’s Margie has the stuff of a great film noir heroine. She’s tough without being hard, street smart, but still emotionally vulnerable, ever hopeful but ultimately fated. She hooks up with the wrong people and makes bad choices every time she turns around. But as in Molly X, we’re drawn to her and suffer with her. In Once a Thief, in which all the characters have unknown pasts and dime-a-dozen lives, Margie is a woman worth a lot more. We desperately want her to escape the daily drudgery and the peril of men like Mitch. By the time Once a Thief comes to its precarious ending, all that’s left is to hope.

In Lady Possessed (1952), Jean Wilson, lies in a semi-conscious state in a private hospital in England recovering from a miscarriage. On her released, Wilson and her husband Tom (Steven Dunne) retreat to a country estate they’ve rented from Del Palma, a well-known British composer and performer (James Mason) whose wife Madeline has recently died.

Jean becomes fascinated by stories of Madeline and the weight of her presence in the house. Jean feels she’s becoming possessed. She begs to leave, but Tom insists she just needs more rest. After attending a concert by Del Palma in London, Jean begins to stalk the composer, convinced that Madeline’s returned in spirit and wants Jean to replace her in Del Palma’s life. Del Palma thinks she’s just another doting female fan of a certain age and sluffs her off as a celebrity seeker. Eventually though he warms to the attention. They start going out and, unaware of her intentions, he invites her to join him on a tour of appearances in European capitals. Jean willingly agrees.

An offbeat suspenser, it’s uncertain in the early going whether Lady Possessed is going to be a psychological thriller or supernatural spine-chiller. Whichever it is, the film is engrossing right up to its heady climax when Del Palma finally comes face to face with the murky circumstances of his wife’s death. Del

Palma is a charismatic but moody character. He’s impatient, arrogant, and

abrasive – character traits made worse by the drinking that follows the loss of

his wife. That said, he has a lot on his plate, not the least of which is

keeping a career going while still grieving and also the insistent and

disquieting presence of Jean to whom he feels a reluctant attraction. Del Palma

increasingly becomes the object of our sympathy and gathering apprehension.

Mason is as good in Lady

Possessed as in any his films

- which is to say, splendid. No one ever played ‘conflicted’ with more

tragic allure and Havoc would never come up against a stronger actor. However,

she holds her own with a performance that’s unflustered and unmannered. Though

Jean winds up heading down the wrong track, it’s clear that she’s not going to

go off the rails. As her infatuation with Del Palma becomes a fait accompli,

her marriage to Tom recedes into irrelevancy – as did personal freedoms in The

Iron Curtain, emotional needs in Chicago

Deadline, or a lover’s life in Once

a Thief. Havoc lived best on-screen within a

transactional film noir universe, even one as perilously out of whack as that

of Lady

Possessed.

The production history of Lady Possessed was itself a famously fraught Hollywood horror story. The film began as an independent production of James Mason and his wife Pamela Kellino for their company Portland Pictures. Mason, now working in the U.S. intended to use funds frozen in England to shoot half the film there then return stateside to finish it. William Spier, husband of June Havoc was brought to work on the screenplay and direct. However, the Masons threw out the script and rewrote it themselves. To add insult to injury, Spier then was blocked by British unions from working in the UK so British director Roy Kellino, ex-husband of Pamela Mason was hired on to do the British sequences. June Havoc was deeply unhappy about taking direction from Kellino so Mason had to step in and take over the picture. But when the production moved to the US, Spier again was sidelined and Kellino once more took over the helm and finished the movie. Meantime, Spier’s former wife, Kay Thompson had been engaged to write some of the music for the film, despite there being no love lost between her and Havoc. The outcome was not a pretty picture but in the end, a decent film noir.

After Lady Possessed, Havoc left films in favor of television, returning to the screen after Spier’s death in 1975. In the 1980’s she toured with a stage show, An Unexpected Evening with June Havoc and in 2003 an off-Broadway space was dedicated as The June Havoc Theater. She died in 2010.

Over the years, Havoc always had been diplomatic when speaking of her mother and sister. But in a 2003 interview, she came clean about her feelings:

“My sister was beautiful and clever –and ruthless. My mother was endearing and adorable – and lethal. They were the same person. I was the fool of the family. The only one who believed I was loved for myself was me.”

Certainly, anyone able to view these six film noirs – movies that define Havoc’s best work on screen – would have no problem in giving her the love and adding this versatile and unconventional actress to a list of female film noir greats. June Havoc has earned her place. All that remains is to give it to her.

Gary Deane

)