By Gary Deane

Her: “You’ll have to be better than this, Gerry. I’ve seen bigger rings on a

peppermint stick”.

Him (lying): “That was my mother’s ring”.

Her: “Your mother’s? I didn’t know that”.

Him: “There’s a lot of things you don’t know, baby.”

Blessed with arrogant

good looks and a rogue charm, Gerard Graham Dennis was

meant to live brazenly. Though born into poverty, his tastes would later run only to the finer things: swank automobiles, bespoke apparel, French champagne,

and beautiful women with models’ cheekbones. Beneath it all, however, lay little

more than a shameless talent for deceit and a reckless willingness to defy the

law.

When still a young teenager in

Southern Ontario in the 1930’s, Dennis was arrested for petty thievery and sent

to reform school. Upon release, he headed for Montreal. It was there he found out it was just as

easy to steal a fortune in valuables as it was kitchen change from coffee cans. One

evening, after robbing an aging gold-mining heiress of $75,000 worth of jewels, he headed to the US with an American girlfriend, Eleanor Harris. Ending up in Westchester County, a leafy and well-to-do enclave just outside

New York City, he took to plundering some of the precinct’s

poshest properties. One night, however, he was caught in

the act by a wealthy New Rochelle boat-builder. Dennis shot him and got away, pockets stuffed with cash and jewelry.

During this period, Dennis also had been

teaching himself how to break up precious stones and remake jewelry so as to avoid the

underworld markdown on stolen goods. He began posing as a legitimate trade rep,

unafraid to ask list prices for his merchandise. Then, in the summer of 1947,

he made his first big mistake. He picked up an attractive young socialite, Gloria

Horowitz, in a Manhattan nightclub and, not long after, sent her out to sell a few of the diamonds

to a jeweler in Philadelphia. A suspicious clerk called the police and Horowitz was

busted while Dennis, out of harm’s way, watched from across the street. The

terrified debutante would spill everything and, for the first time, the cops

had a line on him.

Knowing he’d been

fingered, Dennis left New York for Los Angeles, where he lost no time in setting

up shop. Touring around in a Cadillac convertible or, as the occasion

demanded, a plush Lincoln sedan, he began to woo well-heeled Hollywood celebrities

and bigwigs, representing himself as a prosperous jewelry dealer and aspiring

actor. He was becoming a fixture at parties held in some of the tonier areas of L.A. like Beverly Hills, Brentwood, and Bel Air. There, he was able to case homes at his leisure, then later return to rob them, tracking the owners’ movements by following the

society pages, travel news, and gossip columns. Among his victims were movie

stars Errol Flynn, Alexis Smith, Joan Crawford, Dennis Morgan, and Loretta

Young.

Along the way, he acquired a new

girlfriend, a former school teacher from Toronto, Betty Richie, and in early

1949 told her he was going to divorce his wife back East. He kissed Richie

goodbye and flew to Cleveland to unload a cache of diamonds. As he sat talking

to the jewelry dealer, the man’s nephew walked in, recognized Dennis from a

wanted poster, and ‘phoned the cops. Within minutes they showed up and arrested

him without incident, his only response being, “Well, looks like you fellows

have got me, doesn’t it?” In his pocket was a hand-written list of others whom he'd planned

to rob next, including Charlie Chaplin, Ronald Coleman, Alice Faye, Hedy

Lamarr, Jack Benny, Mary Pickford, Dorothy Lamour, and Louis B. Mayer. A name

crossed was that of Bing Crosby because, as Dennis explained, he was a big fan

of the crooner.

Authorities estimated

that Dennis had stolen over a million dollars worth of valuables since arriving

in Los Angeles. Beverly Hills Police Chief Clinton Anderson expressed grudging admiration

for the robber, saying, “He’s one of the greatest burglars whoever operated.” Dennis

undoubtedly was one of the greatest jewel thieves up until then. But the party

was over. ‘The Raffles of Beverly Hills’ was convicted, sentenced to 18

years-to-life, and sent to Auburn State Prison in Upstate New York to serve his

time, much of it at hard labor.

Closely following the news of Dennis’s

exploits was Warner Brothers producer Bryan Foy, head of the studio’s B unit. Foy’s

career as a creative producer would span 200-plus films, including B noir classics

Canon City (1948), Hollow Triumph (1948), Trapped (1949), Highway 301 (1950), Women’s

Prison (1955), and Blueprint for

Murder (1961). Foy also happened to be a friend of Stanley Church, the beleaguered

mayor of New Rochelle, who had initiated the nationwide search for Dennis.

Church had kept in touch with Foy, providing him updates on the less-than-gentlemanly

bandit whose boldness had profoundly rattled the good burghers of Westchester

County. With Dennis’s arrest getting play in the national media, Foy was primed

to produce a movie about the affair (one in which Church would get to appear as

himself, in an engagingly bouncy performance). Foy then went looking for a screenwriter

who would do credit to Dennis’s fierce criminal adventuring. His pick was

Borden Chase, whose scripts were valued for their straightforward dialog, clearly-outlined

action, and powerful emotion as evidenced by films such as Howard Hawk’s Red River (1948) and Anthony Mann’s Winchester ’73 (1950).

Chase had grown up on the

mean streets of New York in the 20’s and had lived a turbulent life prior to

becoming a writer. He had been gangster Frankie Yale’s chauffeur—at least until

Al Capone had Yale killed. Chase had a native affinity, if not affection, for

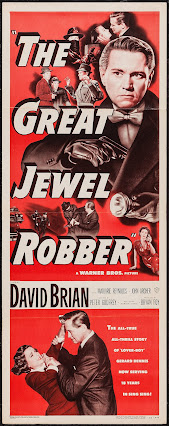

wayward rogues such as Gerard Graham Dennis. In The Great Jewel Robber, he renders

Dennis (played by David Brian) an engaging, living-and-breathing character, despite

his sins, which come fast and furious. By the film’s thirty-minute mark, the

master-thief has been busted for robbery, escaped from prison (where, but for a

sadistic warden, there had been some hope for his reform), acquired forged

documents, crossed the border to the US, planned and pulled off a job, and been

beaten up and hospitalized. Along the way, he’d also enticed a landlord’s

daughter, consorted with countless shady ladies, and seduced a hospital nurse,

Martha Rollins (Marjorie Reynolds) who would become his lover, wife, and, later, accomplice.

David Brian, a fearless Viking

of an actor, bolts through The Great

Jewel Robber with great style, always one move ahead of the authorities and always with

a different woman on his arm. The film’s females are a

glamorous bunch: Perdita Chandler as the cross-border girlfriend who’s as just crooked

as he is; Alix Talton, as a hard-nosed department store buyer whom he picks up in a

hotel lobby in New York; and Jacqueline deWit, playing a haughty Beverly Hill

socialite whom he cultivates and turns into his dupe. Like most of the women

who cross Dennis’s path, each will pay a price, especially Nurse Rollins, who tends

to him while he recovers from a beating and then runs away with him. Because of her caring nature and the fact she loves him, Rollins is vulnerable and it isn’t

long before he begins to abuse her. Forever suspicious and jealous, he says, “You haven’t been doing anything you weren’t

supposed to, have you, you dirty little slut?” and strikes her. Later, as she watches him attempt to pick up a dishy blonde (Cleo Moore), Rollins can only look on with a combination of dismay and resignation. By this time, Dennis’s

maverick appeal has worn out its welcome, and, like Rollins, we’re hoping to see him get what he deserves.

David

Brian was the natural choice to play Dennis, a manipulating cad equal parts suavity and viciousness. Brian had already featured in similar

roles with Joan Crawford in Flamingo Road

(1949) and The Damned Don’t Cry

(1950), and would star with her again in The

Woman is Dangerous (1952). It was Crawford who’d first encouraged Brian, then

a New York stage actor, to come to Hollywood, where he'd have a long career in movies and television. Ironically, Brian would be most rewarded

by both critics and audiences alike for his moving performance as

a fair-minded Southern lawyer who defends a black man facing down a vicious lynch

mob in Intruder in the Dust (1949),

based on a book by William Faulkner. He also played on the right side of the

law as crusading D.A. Paul Garrett in the TV courtroom series Mr. District Attorney, which reprised his

earlier radio role. In real life, Brian was one of Hollywood’s nice guys, known

and respected within the community for his graciousness, musical accomplishment,

and life-long fundraising efforts on behalf of the Volunteers of America, a

charitable organization. There were also few men-about-town who looked so well-attired in a dinner jacket.

The

Great Jewel Robber, its story ‘ripped from the headlines', is

unflinching and intense, with director Peter Godfrey wringing all the drama and

suspense he can out of Borden Chase’s charged script. Three times Dennis is approached

by the authorities just at the moment he thinks he’s in the clear. On one

occasion, police are called to a party at a Beverly Hills residence after a

priceless necklace goes missing. Dennis

has stashed the piece of jewelry in a plant pot but has stayed close by. A

dour-looking cop who’s been sniffing around approaches him and says, “That’s a funny

place to put a thing like that”. A started Dennis starts to move for his gun, just

as the cop says, “I mean, that flower, there”, pointing past him to a towering orchid.

Godfrey had walked on the

dark side of the street before, directing a number of fraught melo-noirs including

Hotel Berlin (1945), The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947), Cry Wolf (1947), and The Woman in White (1948). He would follow

a few years later with one of his tidiest film noirs, Please Murder Me (1956), starring Raymond Burr and Angela Lansbury.

Godfrey had begun his career in live anthology television (Lux Video Theater, The Star and the Story, The Ford Television Theater)

and was a skilled craftsman who handled even lesser material with conviction. Though

a B project by budget and billing, The

Great Jewel Robber often thinks and looks more like an A feature, thanks to Chase’s robust screenplay and Godfrey’s correspondingly forceful point of

view. Occupying similar territory as other great A/B crime titles such as Pushover (1954), Rogue Cop (1954), or Private

Hell 36 (1954), The Great Jewel Robber is a classic

noir crime procedural that still begs to live large once more.

(A longer version of this article appeared in NOIR CITY e-magazine)

.jpg)

.jpg)