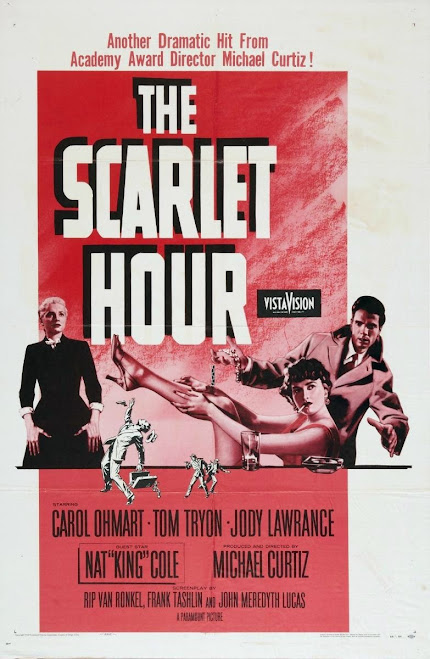

By Gary Deane

When trying to nail down an endpoint of the classic film noir cycle, four titles generally find their way to the head of the line: Touch of Evil (1958) for its baroque inflections of character and style; Odds Against Tomorrow (1959) for its modernist tonal shifts; Psycho (1960) for its narrative and generic dislocations; and Blast of Silence (1961) for its utter moral desolation. In each case, the film represents a defining shift from what had gone before and, in doing so, extends the period’s time frame.

However, it might also be

argued that the real endpoint could be a late-period noir from 1957, which looks back to exactly what had gone before. That film is The Scarlet

Hour, which exemplifies — thematically, narratively, and visually —film noir’s

most resonant motifs, as framed in the 1940s and early '50s: a male

protagonist obsessed with a sexually alluring woman; another female, good,

dutiful, and in love with the man; an urban setting where lives are lived out

unhappily by day and by night; a lurid and convoluted plotline conveyed with

hard-boiled urgency; and a shadowland of expressive and unsettling camerawork.

The Scarlet Hour,

unseen and little known until a few years ago, was produced and directed by Hollywood

great Michael Curtiz, with studio backing from Paramount. However, the film was

released with little fanfare, receiving far wider distribution in the UK than

in the US. After that, it languished in obscurity for more than fifty years,

with little reference to its existence other than some harsh assessments of the

film in the British press, like that in the UK Times:

“(The Scarlet Hour) is a

very drab hour and a half, in the company of actors who have not yet

established their reputations and are unlikely to achieve them as a result of

this movie. The story combines a rather unsavory triangle with a jewel robbery

and the director Mr. Curtiz has achieved a certain amount of suspense but

little else.”

However, to present-day

eyes, The Scarlet Hour isn’t drab at all. It is a deeply noir-stained

tale of dark love, obsession, duplicity, and murder — dense in its generic underpinnings

and saturated with character types that seem both contemporary and

anachronistic at the same time.

Tom Tryon plays E.V. ‘Marsh’ Marshall, the protégé of land developer Ralph Nevins (James Gregory). Marsh also is having an affair with his boss’s wife, Paulie (Carol Ohmart). Paulie wants the life Ralph’s wealth affords her, but she doesn’t want him. Her chance to get away comes when she persuades Marsh to hijack a jewelry heist the two overhear being planned while parked in a lovers’ lane. However, Ralph is aware that Paulie has something going on the side. The plot both thickens and darkens when he decides to do something about it.

That is about as much as

you want to know going in. Much of the pleasure to be had from these tales of

triangulation and treachery is in the details, supplied here by screenwriter

Frank Tashlin, best known for his comedies, including The Lieutenant Wore

Skirts (1956) and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1957). Although The

Scarlet Hour would be Tashlin’s only association with noir, there was a palpable

undercurrent of desperation in his comedies. As observed by writer/ curator Dave

Kehr, “More than most of his contemporaries, Tashlin was attuned to how our

desire betrays us.”

Unfortunately, some of The

Scarlet Hour’s potential is hampered by Tom Tryon’s limited range and a script

that leaves little leeway for his character to connect the dots between virtue

and temptation. A more adroit performer might have found the connection, but the

most Tryon can manage is a hangdog haplessness.

On the other hand, former

model and beauty queen Carol Ohmart was the perfect choice for Paulie, a far

more complex and sympathetic character than noir’s stereotypical femme fatale.

While Paulie uses Marsh and is prepared to betray him, she does so out of

jealousy, not malice. Her actions and betrayals are never that straightforward.

An unusually self-reflexive femme fatale, she goads herself into a criminal act

seeking some nether region of self-worth. Paulie is Double Indemnity’s

Phyllis Dietrichson and Walter Neff combined. With her wintery affect and smoky

voice, Ohmart harkens back to the ‘fire and ice’ sirens of the 40s, but without seeming derivative.

Adding to the mix is Elaine Stritch as Phyllis Rycker, friend and confidante to Paulie. Phyllis is a retired-but-not-quite-reformed B-girl who’s found true love in the arms of a blue-collar hedonist. She and Paulie have a history and through their exchanges, we learn more about who Paulie is and what motivates her. While always dressed to kill, Paulie appears confident, but she’s both damaged and sad with regret. When Phyllis toasts her slightly sozzled husband, “Here’s to happy marriages made in heaven,” Paulie replies, “Here’s to happy marriages made anywhere.” Stritch, always a brash scene-stealer, challenges Ohmart to stand up to her. Ohmart responds in kind and their time together on screen juices up the film.

James Gregory as the

vengeful husband, David Lewis as the jewel heist mastermind (who makes a

memorable reappearance via the film’s bravura plot twist), and E. G. Marshall

and Ed Binns as the investigating police officers were ready-made for film

noir. The four would all go on to become fixtures on the small screen.

Jody Lawrance, playing Nevins’ secretary, Kathy Stevens, is the ‘good girl’ who pines for Marsh, a la

Virginia Huston in Out of the Past. Lawrance does what she can with her

role but, in her bottle-blonde incarnation, begs comparison with Jan Sterling,

a more arresting actress. On the rebound from an aborted launch at Columbia at

the time, Lawrance faded from view in 1961.

Clearly, The Scarlet

Hour doesn’t shy away from its indebtedness to Double Indemnity.

Curtiz pays further respect in a scene where Marsh and Paulie furtively meet up

across the aisle in a record store. Their troubled tryst could easily have

taken place just down the street at Jerry’s Market on Melrose. The script also

has its share of well-turned one-liners, most of them handed to Paulie. Many of

the lines function in the way Walter Neff’s voiceover frames Double

Indemnity. Not only are they memorably hard-boiled, but they also add resonance

to the characters, such as when Paulie says to Marsh: “Don’t try to brush me

off, Marsh — when I stick, I stick hard.” and “I never thought about the

things I wanted, only the things I didn’t want.”

Curtiz’s attempt to

return to the more embellished noir style — one that he’d virtually invented in

Mildred Pierce, embroidered in The Unsuspected (a textbook

example of Foster Hirsch’s notion of “italicized visual moments”) and finally

synthesized in The Breaking Point — was compromised to some extent by a

combination of factors he couldn't overcome. In those earlier films, the

complicated choreography of plot, visuals, and actorly presence meshed into

something greater than the sum of its many parts.

In 'The Scarlet Hour,

all the elements of a top-notch 40s noir are present, as is the framework for a

great and satisfying movie. Unfortunately, the combination of a weaker lead

actor and the ultimate lack of velocity in the film’s final reel means the

component parts manage to not quite fit. However, what we do have is a categorical

study on celluloid of how classic noir was supposed to operate, The Scarlet

Hour unquestionably is the last honorable attempt to build a noir from the

classic recipe. The film also can be seen as a look into the ‘what if’ career

of Carol Ohmart, in every sense a compelling actress who was made for a style of

film style on the verge of extinction — just as she was offered the chance to

be the very embodiment of it. Ohmart’s portrayal of icy, sexual cunning brings

the arc of the true noir cycle to a close — an arc that would not be revisited

until Body Heat (1981) nearly a quarter-century later.