Mickey Rooney was too big to

fail.

For nine decades Rooney was

never more than steps away from the footlights or the limelight. When he died in 2014 at age 93, the little actor with the outsized personality left behind

an amazing 340 screen credits, an Emmy, two Oscars, and a pair of Golden Globes.

From the mid 1930’s to the post-war 1940’s Rooney was among the biggest movie box office draws in the world. Starring in a series of films as Andy Hardy, the go-getting teenage son of a small-town judge, Rooney won hearts the world over with his on-screen display of inexhaustible exuberance and equally boundless talent.

From the mid 1930’s to the post-war 1940’s Rooney was among the biggest movie box office draws in the world. Starring in a series of films as Andy Hardy, the go-getting teenage son of a small-town judge, Rooney won hearts the world over with his on-screen display of inexhaustible exuberance and equally boundless talent.

However, the war changed

everything and Rooney, now well into his ‘20’s and still looking like a

pug-faced kid, knew he had some growing up to do. First efforts in that direction

were sports pictures: ‘Killer McCoy’ (1947), a boxing story; ‘The Big Wheel’ (1949), a race car drama; and ‘The Fireball’ (1950), based

on a novel by Horace McCoy (‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’) about pro roller derby.

Though providing decent entertainment, the movies remained extensions of what had gone before, with Rooney as the unabashed little world-beater who, after finding humility in defeat, would emerge a champion. Unfortunately audiences no longer seemed to care. Rooney's brand had become stale and confused. In order to revive his career, it was now critical that he find whatever path he could to greater maturity and restraint both on and off the screen.

Though providing decent entertainment, the movies remained extensions of what had gone before, with Rooney as the unabashed little world-beater who, after finding humility in defeat, would emerge a champion. Unfortunately audiences no longer seemed to care. Rooney's brand had become stale and confused. In order to revive his career, it was now critical that he find whatever path he could to greater maturity and restraint both on and off the screen.

By 1950, having left MGM and without

a contract, Rooney had become yesterday’s news. Nearly broke, he had to take

what would be on offer, including a succession of low-budget noir dramas featuring

Rooney in starkly memorable portrayals of raw ambition, desire, obsession, betrayal,

greed, and moral disintegration.

1. ‘QUICKSAND’ (1950)

“I feel like I'm bein' shoved into a corner, and if I don't get out soon, it'll be too late. Maybe it's too late already!”

Dan Brady (Rooney) works as a

grease monkey at a Santa Monica garage. He’s got an on-again-off-again

girlfriend (Barbara Bates), though thoughts of settling down with her don’t appear

to spark his plug. Then one day at the local diner, a new counter-girl walks in

who does. She’s called Vera (a hard name for a hard-edged blonde played by

Jeanne Cagney) and he asks her out. Strapped for cash, he takes twenty dollars from the garage till, intending to put it back before it’s

missed.This petty theft sucks Brady down into a vortex of crime - assault

and battery, armed robbery, extortion, car theft, murder, kidnapping - and a

world of pain, every bit of it deserved.

Directed by Irving Pichel (‘They Won’t Believe Me’ 1947) and shot by Lionel Linden (‘The Scarlet Hour’ 1956, ‘The Big Caper’ 1957, ‘I Want to Live’ 1958), 'Quicksand' sounds like a lot to swallow but the film's brisk resolve renders it all not only plausible but inevitable. Vera wants a mink coat and Brady wants to buy it for her. Brady’s boss (Art Smith) wants payback for a car he’s stolen but at a big premium. Vera wants Brady to take what they need off a greasy penny arcade operator, Nick (Peter Lorre) who's blackmailing Brady. One sorry want leads to another.

In fact, Brady’s a ready chump and

just as crooked as Vera. He's just too thick and unaware to realize it. Like everyone

else in the movie he’s small and grubby and it’s no longer fate that condemns them but the smallness and grubbiness

of their ambition.

Mickey Rooney’s playing against type in the film works as well for him as he does for it. Elements of his cocksure little self are present but as things unfold we see sides of Rooney, the actor, which weren’t so apparent. At the time of release ‘Quicksand’

sank without a trace; fortunately it fell into the the public domain and now is among the better known of Rooney’s

film noirs.

2. ‘THE STRIP’ (1951)

“You talk pretty big for a little man”

Stanley Maxton (Rooney), who's just

out of the service, heads to Los Angeles to find a job. He gets hooked up with

a bookie operation headed by Sonny Johnson (James Craig) and then meets Jane

Tafford (Sally Forrest), an aspiring actress, dancer and cigarette girl and in

a club called ‘Fluff’s’. Stan used to be a jazz drummer and jumps

at a chance to join the club’s house band. But then who wouldn’t want to sit in with

Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden and Earl ‘Fatha’ Hines?

So far, so good. However, Stan

makes the mistake of introducing Jane to the debonair Sonny who promises some

studio introductions. Stan tries to warn her off but she won’t listen. He tells

Sonny to back off and threatens to expose Sonny’s bookmaking set-up if he

doesn’t. Things get nasty and people get hurt. Some even get killed.

‘The Strip’, directed by

Leslie Kardos (‘The Tijuana Story’ 1957) and billed bizarrely as ‘MGM’s Musical

Melodrama of the Dancer and the Drummer’ is more noir drama than musical. Meantime,

there are long-ish musical interludes and how you feel about that depends on how you feel about classic renditions here of ‘Basin Street Blues’ by jazz

luminaries like Armstrong, a young Vic

Damone warbling a wistful and warm ‘Don’t Blame Me’ and Forrest herself in a

couple of rousing, hip-shaking dance numbers expansively shot by Robert Surtees

(‘The Bad and the Beautiful’ 1952). But the drama holds its own, helped along

by seasoned character actor William Demarest as avuncular club-owner, Fluffy, and James Craig as the double-dealing Johnson.

Rooney is fittingly attentive and subdued in 'The Strip'. Stan is naive and unprepared and the flashback structure of the story serves to emphasize his helplessness. In the memorable closing scene, he returns to the club and retreats to his drums in an attempt to relieve the anguish. It’s a touchingly open moment that suddenly makes the movie something much more that it had been.

3. 'DRIVE A CROOKED ROAD' (1954)

“Do you have $15,000? Well, I can’t wait. I know what happens when people wait!”

On Sundays Eddie Shannon is a

big man on the amateur auto-racing circuit. The rest of the week he’s small

potatoes and he knows it.

The fact is, Barbara’s slick-dick

boyfriend, Steve Norris (Kevin McCarthy) and his smartass sidekick Harold Baker

(Jack Kelly) need Shannon to be the wheelman on a bank job they’re planning. At

first Barbara’s willing to play the honeypot. But when

he agrees to go along (only because he thinks that's what Barbara wants) she

begins to feel sorry for him and regret her involvement. Things start to get

complicated and stay that way.

Deliberately-paced and low on melodrama, the film is not so much interested in the robbery as what occurs immediately before and afterwards. Close to meditative at times, ‘Drive a Crooked Road’ feels like a film noir made in France.

Deliberately-paced and low on melodrama, the film is not so much interested in the robbery as what occurs immediately before and afterwards. Close to meditative at times, ‘Drive a Crooked Road’ feels like a film noir made in France.

According to Rooney’s

autobiography ‘Life’s Too Short’, one of the reasons that he wanted a deal with

Columbia after being released by MGM was the chance to do a picture with

Richard Quine (‘Pushover’ 1954). The young director already was seen as good with actors and ‘Drive a Crooked Road’, scripted by Blake Edwards is very much an actors’ picture.

4. 'BABY FACE NELSON' (1957)

“More vicious than ‘Little Caesar! More savage than

‘Scarface’! More brutal than ‘Dillinger’! The baby-faced butcher who line ‘em

up and chopped ‘em down and terrorized a nation!” (poster taglines)

As attitudes in crime films and

film noir began to harden in the late 1950’s there was renewed interest in the

gangster movie which had settled as a genre in the 1930’s. However, the gangster as tragic hero left the

building during the orgy of uncontained violence that erupted in 1957 with ‘Baby

Face Nelson’ and continued on with copy-cat true-crime titles, ‘The Bonny

Parker Story’ 1958, ‘Machine Gun Kelly’ 1958, ‘The Purple Gang’ 1959, ‘The Rise

and Fall of Legs Diamond’ 1960, ‘’Al Capone’ 1960’, ‘Ma Barker’s Killer Brood’ 1961’,

‘Portrait of a Mobster’ 1961 and ‘King of the Roaring ‘20’s: The Story of Arnold Rothstein’ 1961. But none

were as perturbing as ‘Baby Face Nelson’ starring Mickey Rooney. For a start, none

were about anyone quite as unhinged as the real-life Nelson, born Lester Gillis.

Gillis was in juvie by the

age of twelve, though the movie opens with his release from Joliet prison in

1933. He soon reverts to form, with his

girlfriend, Sue Nelson (a fictional creation played by Carolyn Jones) along for

the ride. Gillis runs afoul of mob boss Lou Rocca (Ted de Corsia) by refusing

to do a hit. But Rocca has it done anyway and frames Gillis for it. Gillis is

arrested but with Sue’s help makes a break and returns to Chicago to kill Rocca.

He's shot during a robbery and while getting fixed-up by a drunken sawbones

(Cedric Hardwicke) meets John Dillinger (Leo Gordon). It’s Dillinger who starts

calling him ‘Baby Face’ (he’d already adopted the name Nelson as an

alias). Dillinger and Nelson team up to rob banks but Dillinger is murdered and

Nelson takes over. Now he’s Public

Enemy Number One and determined to live up to the billing.

Rooney is fearless as Nelson

in a performance that goes toe-to-toe with Jimmy Cagney’s in and

‘Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye’ (1948) and ‘White Heat’ (1949). Rooney’s Nelson is pure, uncontrolled aggression -

which it’s inferred arises from his obsessive little-man complex (the only

person Nelson doesn’t kill during several robberies is a bank manager who’s

shorter than he is).

‘Babyface Nelson’ is easily the

most impressive entry of the late 50’s gangster noir cycle. With a script by Daniel Manwaring (‘Out of the

Past’) and made on the cheap by director Donald Siegel in just 17 days, this

fragmentary and revisionist biopic is raw and twitchy. It’s one of the best

early examples of Siegel’s uncompromisingly stripped and intense style, one which would

inform Clint Eastwood as an actor and later as director.

5. 'THE COMEDIAN' (1957)

“Don’t make me the heavy all the time! Shut up back

there, I’m talking!"

As television kicked the legs

out from under the careers of even the biggest movie stars in the 1950’s,

most were able to pick themselves up and make peace with the enemy – some of it

lasting. Many found new acclaim with appearances on 'anthology series' such as

CBS Playhouse 90, a weekly program of live hour-and-a-half-long studio dramas

that ran from 1956 to 1961.

The ‘Comedian’ is one of many

noir-stained productions that would become TV touchstones of the period. Written

by Rod Serling (who won an Emmy for the script) and directed by a young John

Frankenheimer, it's a searing, behind-the-scenes look at Sammy Hogarth (Mickey

Rooney), an abusive and egomaniacal comic genius who makes life hell for everyone

within distance. Hogarth’s main victim is his weakling brother, Lester (Mel

Torme), whom Sammy ridicules in the opening monologue of his show each week.

No one gets off easily,

including Lester’s put-upon wife Julie (Kim Hunter) and Al Preston (Edmund

O’Brien), Hogarth’s lead writer. Preston despises Hogarth and also increasingly

himself. He’s no longer sure that has what it takes - if he ever did. Desperate,

Preston submits a script he didn’t write but one he hopes will buy him time. Added to the sulferous mix is gossip

columnist Otis Elwood (Whit Bissell), another favorite target of Hogarth’s

sneering put-downs. In revenge, Elwood exposes Hogarth’s shadowed liaisons with

Lester’s wife.

It doesn't matter. Hogarth may be without a friend but

he settled that deal long ago. If that’s what it takes to have his monstrous

need for adulation fed on demand, then so be it. Rooney is

unshrinking in his portrayal of Sammy whose wounding anger goes unexplained,

leaving limited room for sympathy. Eventually maybe he’ll pay in hell for his abusive behavior and suffocating

fraudulence. Though by the end of ‘The Comedian', it's clear it'll take at least that long to settle accounts.

6. ‘THE LAST MILE’ (1959)

“Maybe there’s a better place somewhere. They’re sure

oughta be!”

‘The Last Mile’, about an attempted breakout

from death row, is based on a 1930 stage play and for much of the first half the

film does little to disguise its theatrical origins. This makes for slow going,

with on-set movement confined to that of the prisoners in their cells. ‘The

Last Mile’ finally comes alive as a movie when inmate John Mears (Mickey Rooney)

reaches through the bars to put a chokehold on one of the guards. He grabs the guard’s

key-ring and soon the convicts are out of their cells. They find guns and

ammunition and launch their assault against the tower gaurds in one of the most famously ferocious fire-fights in classic noir.

And so it goes, until the warden refuses Mears’ ultimatum and Mears executes one of the guards (Don ‘Red’ Barry), shooting him point blank as he begs for his life. At that point, we become less concerned about prison reform and the death penalty than about who’s going to get it next.

Mears is a deranged murderer

with a hate-on for the world and ultimately deserves whatever is coming to him.

Nevertheless, as twisted as Mears might be, Rooney still manages to invest

him with enough humanity to make us care. It’s a bravura showing by the

actor, who now looks his age and as physically hard and imposing as he ever

will.

Though the ‘The Last Mile’

was made on the cheap, director Howard Koch (‘Shield for Murder’ 1954, ‘Big

House U.S.A.’ 1955) and cinematographer Joseph C. Brun (‘Odds Against Tomorrow’

1959) brings atmosphere and surprising style to this late-period noir with some evocative

framing and lighting. Composer Van Alexander who scored ‘Baby Face Nelson’ and

two other films here inserts a keyed-up jazz score.

But by the end of

production, ‘The Last Mile’ was viewed by the studio as a being a

‘New York’ film i.e. a violent and soul-searing psychodrama that wasn’t looking

for an audience. The film was given an apathetic release, making sure

it never found one.

7. THE BIG OPERATOR(1959)

“Listen, you don’t set anybody on fire unless I tell

you to! Understand?”

The night before a hearing on

racketeering charges against corrupt union organizer, Little Joe Braun (Mickey

Rooney), the court’s chief witness is killed by Braun’s henchman, Oscar Wetzel (aka

‘The Executioner’), played by Ray Danton. When he delivers the witness’s files

to Braun, he says he thinks a couple of Braun’s own members, Bill Gibson

(Steve Cochrane) and Fred McAfee (Mel Torme) may have seen the handoff take

place. Braun figures he can head off any trouble by offering them cushy office

jobs with the union. But the pair is wise to what’s going on and tell Braun to

forget it. Of course, that’s not the answer he wants to hear and things do not

go well for the boys. McAfee is beaten up and set alight and Gibson is later kidnapped and tortured. It's tough stuff.

Though all the movies here are from the B side of the tracks, ‘The Big Operator’ is the first one that really feels like it. The sloppy screenplay by Paul Gallico and Charles Haas’s overly-hurried direction make it visibly hard on everybody, especially Ray Danton as Braun’s inexplicably hapless hitman (before there was George Clooney there was Ray Danton!). It’s definitely not a movie at ease with itself.

On the other hand, if you’d never seen Mickey Rooney before you might assume that this was the performance of a lifetime. Rooney is terrific in another larger-than-life gangster part demanding an equally larger-than-life effort from the actor.

The rest of the cast, some of them curiously interesting choices, also pull their weight: Mamie Van Doren playing against type (more on that later) as Cochrane’s sensible spouse; Mel Torme as a blue-collar working stiff; and Jim Backus as labor investigator, Cliff Heldon. And although Rooney is the magnetic center of things, screen time is shared with film noir favorite Steve Cochrane whose easy-going character likes his job, adores his wife and son, and lives a modest, cautious life. But when the time comes to deal with Braun, he does so and without heroics. Cochrane gives a thoughtfully tone-downed performance, reflecting his range and proving again that Michelangelo Antonini had seen something more than just ‘Steve Cochrane’ when casting him in ‘Il Grido’ two years prior.

Despite the doubtfulness of the script, ‘The Big Operator’ at least is never drab. Mickey Rooney would never let that happen. While there’s not a whole lot of money up on the screen, what's there is more than enough to cover the price of admission.

On the other hand, if you’d never seen Mickey Rooney before you might assume that this was the performance of a lifetime. Rooney is terrific in another larger-than-life gangster part demanding an equally larger-than-life effort from the actor.

The rest of the cast, some of them curiously interesting choices, also pull their weight: Mamie Van Doren playing against type (more on that later) as Cochrane’s sensible spouse; Mel Torme as a blue-collar working stiff; and Jim Backus as labor investigator, Cliff Heldon. And although Rooney is the magnetic center of things, screen time is shared with film noir favorite Steve Cochrane whose easy-going character likes his job, adores his wife and son, and lives a modest, cautious life. But when the time comes to deal with Braun, he does so and without heroics. Cochrane gives a thoughtfully tone-downed performance, reflecting his range and proving again that Michelangelo Antonini had seen something more than just ‘Steve Cochrane’ when casting him in ‘Il Grido’ two years prior.

Despite the doubtfulness of the script, ‘The Big Operator’ at least is never drab. Mickey Rooney would never let that happen. While there’s not a whole lot of money up on the screen, what's there is more than enough to cover the price of admission.

8.

'PLATINUM HIGH SCHOOL' (1960)

“Look, I’m sick of this. I’m going to find out the truth for myself, whatever the truth is, good or bad!”

With a title like ‘Platinum High School’, it's a good bet the movie might feature Mamie Van Doren as a slutty switchblade sister. At least, we hope it would. But’s it’s not that kind of movie and not that kind of high school. Black Rock is an expensive private military academy, a ‘rich kid’s penitentiary’ for incorrigibles located on ‘Sabre Island’ (Catalina Island) off the coast of California. It’s run by Major Kelly (Dan Duyea) along with Jennifer Evans (Terry Moore), his School Assistant and piece-on-the-side, and Hack Marlow (Richard Jaeckel), one of several hard-ass ex-marines hired to keep the spoiled punks in line.

Steve Conroy (Mickey Rooney) shows up on the island unannounced, wanting to find out more about the death of his son, Steve Jr. But no one wants to talk apart from Harry Nesbit (Elisha Cook Jr.) the local hash-slinger and barkeep and Lorinda Nibley, the mute storekeeper’s daughter played by a stirringly beautiful eighteen year-old Yvette Mimieux.

Steve Conroy (Mickey Rooney) shows up on the island unannounced, wanting to find out more about the death of his son, Steve Jr. But no one wants to talk apart from Harry Nesbit (Elisha Cook Jr.) the local hash-slinger and barkeep and Lorinda Nibley, the mute storekeeper’s daughter played by a stirringly beautiful eighteen year-old Yvette Mimieux.

It doesn’t take long for Conroy to outstay the little welcome he’s already had. Conroy is assaulted and shot at by goons including several senior classmen – among them, Billy Jack Barnes, a noxious redneck delinquent played by Conway Twitty. However Conroy, also a former marine is ready to give as good as he gets. Eventually he uncovers the truth and sets out to bring Kelly and crew to justice.

After picking up their checks, everyone involved in the movie likely was happy to be done with it. That would include producer Albert Zugsmith and director Charles Haas for whom such exhilaratingly peculiar drive-in features were just another day at the office.

But no matter how wondrously improbable the story or inept the filmcraft, Mickey Rooney does not seem to notice or care. As earnestly professional as always, Rooney delivers a somber and convincing performance as the aggrieved father. On the other hand, Dan Duryea doesn't look half as sure of himself which only affords Rooney greater stature in every sense. 'Platinum High School’ might be the first film in which Rooney's size doesn’t even register.

David Thomson in his ‘The New/ Biographical Dictionary of Film’ contends that Rooney had the ability to bring magnitude to the very least of his movies. Among them is ‘Platinum High School’, a film in which Thomson declares Rooney’s performance to be "brilliant". It’s a bold claim but in no way an outrageous one.

9. ‘THE KING OF THE ROARING '20'S: THE STORY OF ARNOLD ROTHSTEIN' 1961

“When you’re married to a gambler, the only game you

ever get to play is solitaire!”

David Janssen stars in this

plodding biopic that tries to tell the story of legendary gambling kingpin Arnold

Rothstein but doesn’t do much of a job of it. If Jo Swerling’s screenplay ever contained

a dramatic arc, it had fallen flat by the time the production went to

set. The uncharacteristically pedestrian, paceless direction of Joseph M. Newman

(‘Abandoned’ 1949, ‘711 Ocean Drive’ 1950 ) does nothing to help things along.

The main problem is

Janssen, a highly watchable but restricted actor who’s unable to find a way to

bring charisma to a gangster who apparently didn’t have any of his own. The

picture’s supporting players including Rooney, Dianne Foster, Jack Carson, Dan

O’Herlihy, and Keenan Wynn do much better - as do William Demarest, Regis

Toomey, Diana Dors and Robert Ellenstein, all of whom make interesting appearances.

However, it’s really only Rooney who’s able to find a palpable heartbeat in this bloodless

drama.

Rooney plays Johnny Burke,

Rothstein’s loyal sidekick and partner-in-crime since childhood. As Rothstein

becomes more powerful and forms new alliances, Johnny is no longer worth it to the mob and has to be eliminated.

While Johnny is a willing party

to the crime and corruption, he’s a pointedly sympathetic character to whom Rooney

provides a touching moral dignity. The few scenes in the movie with any emotional honesty are those in which Rooney appears. Accordingly the opening

credits of the film end their scroll with “And featuring Mickey Rooney”. Though

Rooney plays second fiddle in ‘The King of the Roaring ‘20’s’, he’s really the only fiddle here worth the listen.

10. '24 HOURS TO KILL' (1965)

“Drink up, Captain. You will need it when you hear

what I have to say.”

Norman ‘Jonesy’ Jones (Mickey

Rooney) is a crew member on a passenger jet that’s forced to land in Beirut due

to engine trouble. Repairs will take about 24 hours, leaving Jones, Captain

Jamie Faulkner (Lex Barker), co-pilot Tommy Gaskell (Michael Medwin) and a bevy

of bouncy stewardesses with time to kill. No problem, except for Jonesy who

suddenly becomes nervous and evasive - because Beirut is actually the last place

he wants to be.

Norman Jones is a gold

smuggler who inadvisably lifted a shipment for himself and now is on the run

from Middle-Eastern mob boss Malouf (Walter Slezak). Faulkner and his crew get

dragged into his mess without really knowing what’s going on. That is, until

Malouf kidnaps Faulkner’s girlfriend (Helga Sommerfield) in a cut-throat

attempt to force everyone’s hand.

‘24 Hours to Kill’, with its trippy ‘60’s Euro-spy trappings, exotic locales, coiffed babes in bikinis, arch villains

with accents and a suave alpha-male at the controls makes much of its foreign frisson. British-born director, Peter

Bezencenet capitalizes on the splendors of Beirut, ‘The Paris of the Middle

East’ before it became an eternal war zone.

However ’24 Hours to Kill’ again belongs mostly to Mickey Rooney and is another kick in the teeth to the breezy, affable character types with whom he’s forever associated – despite these outings as a guileless chump, petty criminal, righteous avenger, and merciless mobster. In ’24 Hours’ he adds another and different kind of criminal psychopath to the list.

While Rooney seems to be a decent chap on good terms with everyone, Barker trusts him for too long, as the pilot scrambles to try and protect himself and his crew. But no one could know how much of a liar and moral coward the little purser really is. Rooney is chilling as the ugly layers of his deceit are peeled back.

Rooney is the best reason to watch ’24 Hours to Kill’ but he's not the only one. There’s a surprise ending which actually is a surprise - except to the Malouf, who while incanting, “Man proposes, Allah disposes” is seeing to it that Allah lives up to his word.

While Rooney seems to be a decent chap on good terms with everyone, Barker trusts him for too long, as the pilot scrambles to try and protect himself and his crew. But no one could know how much of a liar and moral coward the little purser really is. Rooney is chilling as the ugly layers of his deceit are peeled back.

Rooney is the best reason to watch ’24 Hours to Kill’ but he's not the only one. There’s a surprise ending which actually is a surprise - except to the Malouf, who while incanting, “Man proposes, Allah disposes” is seeing to it that Allah lives up to his word.

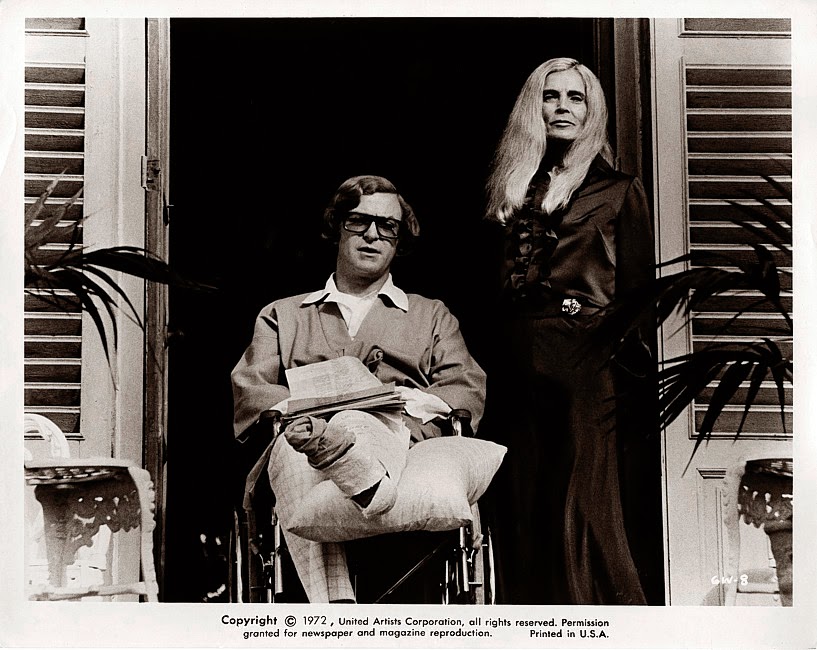

11. ‘PULP’ (1972)

“It looked like her honor was on the missing list. So

was her cash. I got the feeling it was way too late to retrieve either.”

A goof ball attempt at noir comedy, 'Pulp affectionately parodies the noir gangster movie, much as ‘Gumshoe’ starring Albert

Finney burlesqued the private-eye genre a year earlier.

Mike Hodges directs and

Michael Caine stars as Michael King a writer of trashy pulp novels who’s hired

by Preston Gilbert (Mickey Rooney) to ghost his memoires. Gilbert’s a former

Hollywood star living in exile in Malta along with characters played by Lizbeth

Scott, Lionel Stander, Al Lettieri, Dennis Price and others. When Gilbert is

murdered, King becomes an amateur sleuth and a sore thumb in the eye of mafia

types who were determined to make sure they didn’t show up in Gilbert’s

autobiography.

The movie is more ‘Get Smart’

than ‘Get Carter’. Some of it works and some of it doesn’t. Finding and

keeping a comfortable balance between sharp-elbowed parody and soft-hearted tribute

is never easy. But something that both lovers and haters of the film seem to

agree on is that Mickey Rooney’s eager and flamboyant send-up of himself makes

'Pulp' worth a look.

___________

“I don't regret anything I've ever done. I only

wish I could have done more.”

Of all the remembrances of Mickey Rooney in the major media following his death, only a handful mentioned any of the films highlighted here.

Fair enough. They’re small productions, some an effort to find, and and usually of interest to committed fans of Rooney and/or film noir.

However, even within the film noir community appreciation of Rooney isn’t outright. For some, it's distaste for Rooney's public antics, his loud-mouth politics, and infamous relationship history. But as Ava Gardner said, “I loved him because he made me laugh”. Rooney made plenty of people laugh (and often love him), including those who found it hard to tolerate his excesses. He was who he was and if anyone were hurt along the way, it was often Rooney who got the worst of it.

Others just resist crediting Rooney as a noir actor and leading man, as he favored genial parts in so many genial movies and stage productions for most of his career. In other words, he wasn't a Robert Ryan, Robert Mitchum, Robert Montgomery or even Robert Young, all actors better able to fulfil urgent hardboiled hopes of them as noir protagonists and heroes. As well, Rooney was cast mostly as a villain in the noirs in which he starred, relegating him to creepy character status e.g. Elisha Cooke Jr. or Percy Helton or Peter Lorre in the minds of some.

Others just resist crediting Rooney as a noir actor and leading man, as he favored genial parts in so many genial movies and stage productions for most of his career. In other words, he wasn't a Robert Ryan, Robert Mitchum, Robert Montgomery or even Robert Young, all actors better able to fulfil urgent hardboiled hopes of them as noir protagonists and heroes. As well, Rooney was cast mostly as a villain in the noirs in which he starred, relegating him to creepy character status e.g. Elisha Cooke Jr. or Percy Helton or Peter Lorre in the minds of some.

But this fails

to give full due to the fact of Rooney’s extraordinary starring presence and command of craft

in these films. As John Frankenheimer

after being with Rooney on ‘The Comedian’ said of him, “Mickey Rooney is the

most talented person I have ever worked with or will ever work with.” Others were

just as admiring. James Mason when asked who was the best

actor in Hollywood replied, “Mickey Rooney”; likewise, Sir Lawrence Oliver in answer

to the same question. Clarence Brown who

directed him in ‘The Human Comedy’ and ‘National Velvet’ said, “Mickey Rooney could

be a jerk but he was the closest thing to a genius I ever worked with."

None of these lowly B noirs are accepted masterpieces. But the genius to which Clarence Brown referred

is there in every frame in which Rooney appears and insists on a more generous view of the actor as a legitimate noir icon, however singular. Despite

whatever awards for the musicals and ‘The Human Comedy’ or ‘The Adventures of the Black Stallion’ (1979) and 'Bill' (1981), it’s far more likely to

be Rooney’s film noirs that are most screened at festivals and to be seen eventually by more people than ever may have heard of his other films.

As Rooney said towards the

end of his life, ‘I don’t retire, I inspire’. From anyone else that would sound

like conceit. From him it was the unassailable truth. But the little actor’s towering,

inspiring performances in these films speak for themselves. It would be a shame

not to listen.

Written by Gary Deane

.jpg)